South American annual killifish (Austrolebias, Notholebias, among others) remain a rarity in the hobby due to their specialized reproductive biology and the mandatory egg diapause. However, many of the 210+ species prove more hardy and long-lived in home aquaria than their 'annual' label implies. Originating from ephemeral pools, these fish require specific parameters to thrive. This guide details the necessary care and incubation techniques to help aquarists successfully maintain and propagate these unique species.

Introduction

Although many aquarists are engaged with South American annual Killifish, they have remained somewhat uncommon for the majority of hobbyists. This is partly due to the fact that these species are hardly available in the local fish stores. Furthermore, they pose certain requirements regarding the knowledge and patience of their caretakers in practice, due to their reproductive biology.

In recent years, many more species have been discovered, which has further intensified interest in this fish group. Among these new discoveries, there are particularly beautiful fish. Unfortunately, articles about these species usually only introduce the various species and provide only a brief overview of breeding. However, among the many species now introduced into the hobby, there are highly varying requirements. Therefore, I would like to elaborate a bit more on their needs in this article, as well as on the path to successful reproduction, while only touch upon systematic questions tangentially.

Living beyond a single summer

Old prejudices persist longer and are often repeated. In the early days of aquaristics, many breeders failed with these species. The myth of their short lifespan was born, which only truly applies to a few species. So far, over 210 species have been described that can withstand aquarium conditions well. But first, let’s take a closer look at which fish we have before us.

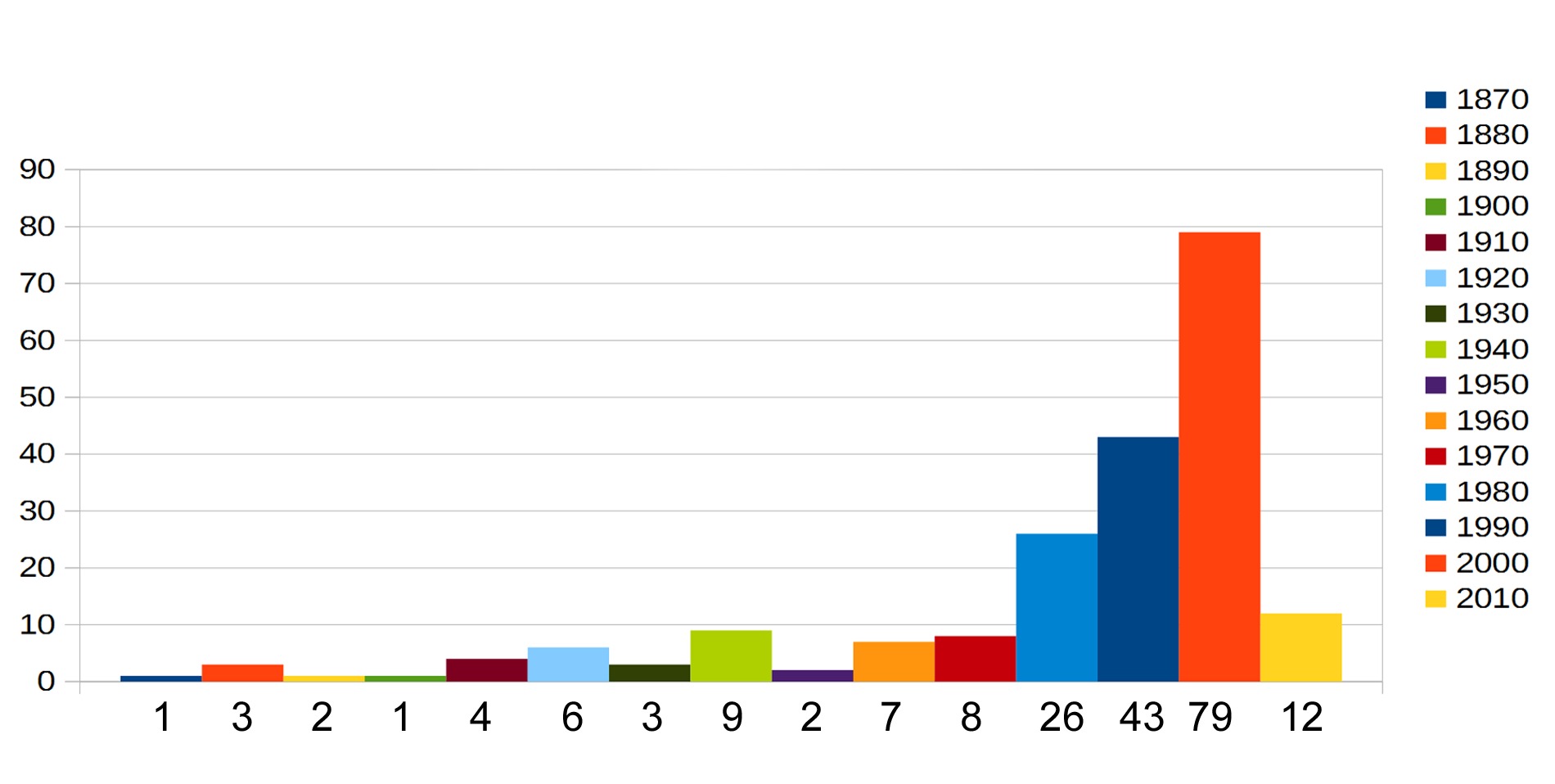

Tab.: The first descriptions of South American annuals are distributed over different time periods.

South American annual Killifish belong to the family Rivulidae (Order Cyprinodontiformes Berg, 1940, Suborder Aplocheiloidei Bleeker, 1859). This family name was disputed. It is based on the tribe name Rivulini, which Myers assigned in 1925 and from which Parenti (1981) derived their proposal for the family name. In the meantime, the Commission on the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN, 1999) accepted the request to rename the affected moth subfamily, allowing Rivulidae to be used again (worldfish wiki, 2025).

Their habitats are waters that adapt in their dimensions to the rainy and dry seasons, usually drying out completely on a regular basis. The life cycle of these fish is completed between one year and about two and a half years. What is special about our annual Killifish is up to three diapauses, which the eggs undergo while maturing into juvenile fish. During these times, their metabolism slows down significantly. The juveniles grow very quickly. The sexually mature individuals begin laying eggs a few weeks after hatching. These fish age relatively quickly and usually die when their waters dry up.

By now, we know that these fish are not quite as short-lived as has often been assumed. Several species outlive the popular guppies by a significant margin. For instance, Austrolebias bellottii and Argolebias nigripinnis die after about 14 months, in some cases 18 months. A notable portion of Notholebias fry still swims after more than two years. And currently, Maratecuara splendida continues to swim its rounds with me after more than two years, even though signs of aging are visible.

Habitats

South America is characterized by large-scale habitats such as the highlands of Guyana, the Brazilian Highlands, or the Andes. However, a special position is held by the Amazon Basin. There, more water evaporates from the animal and plant world as well as from soil and water surfaces than over the tropical Atlantic. This leads to significant precipitation in the western Amazon Basin.

In the discovery history of our South American annuals, it is noticeable that initially, mainly species were found in the coastal region of the continent (exception e.g. Cynolebias porosus Steindachner, 1876). Gradually, further occurrence areas were explored. Until 1979, only 49 species had been described. Then scientific interest also awakened in the home countries of these killifish, particularly Brazil. Meanwhile, more than the already mentioned 210 species have been described.

In eastern Brazil, a coastal mountain range stretches from the north deep into the south. Throughout the year, the varying intensity of rainfall leads to the seasonal formation of puddles.

Fig.: View of Rio de Janeiro: The clouds coming in from the Atlantic rain down here in eastern Brazil at the coastal mountain range.

As a habitat for the annual Killifish, the Brazilian Caatinga has often been discussed due to collecting activities and the resulting first descriptions by Costa. In such a region with a semi-arid climate (from Latin aridus = dry, arid/semi-arid), evaporation exceeds precipitation for six to nine months of the year. Semi-arid is therefore a designation for areas and climates characterized by the occurrence of a marked dry season, but which also have about three to five humid months throughout the year. During this short time, rivers may carry water periodically or episodically. Similar conditions apply to the Brazilian Cerrado.

Overall, it makes sense to examine the local conditions based on the first descriptions or travel reports for hints on care and breeding. Pillet (2008) provided a good overview of the locations he encountered in Brazil. The water of these ponds and puddles is, with few exceptions, generally very soft, between 9 and 200 µS/cm. In forested areas, the water temperatures are lower than in open terrain, 20°C to 30°C are encountered with a pH value of 5 to 7.

Care

The South American annuals can be kept well in the aquarium. I will address the requirements for breeding separately. With such a wide distribution of species, very different parameters of collection sites are naturally encountered. This means that individual collection conditions in water values can vary significantly. In Venezuela, Thomerson, J.E. & Taphorn, D.C. (1987) found a conductivity of up to 3200 µS/cm at collection sites of Austrofundulus limnaeus (similar to Rachovia hummelincki - in flowing water - up to 2000 µS/cm). Whether saltwater was similarly introduced by wind, as with other species of the genus, is difficult to assess given the occurrence far from the sea. Salt increases conductivity but is not a hardness contributor.

Water changes are a matter of course in care. They are important for the well-being of our charges. Within limits, the fresh water can differ from the exchanged water. Filters and aeration can support water care. The water should only be moderately moved. We do not have endurance swimmers before us. Whether a lot or little light falls into the holding or breeding tank seems initially secondary. Therefore, when looking into the killifish cellar, no one will be surprised that most tanks are unlit. Not all species occur in open terrain. Additionally, we should consider that light intensity affects coloration. A Notholebias minimus as a forest dweller will show larger portions of a greenish coloration under subdued light. Otherwise, brownish portions will make the fish appear darker. Many aquarists have used this influence of light intensity on pigmentation in recent years during temporary outdoor keeping to bring back more intensively colored fish in the fall. Some refer to it as summer freshness.

Space factor

The final size of the species gives a guideline for the housing of the animals. We must keep in mind the broad spectrum of fish we are talking about. For smaller species, a standard aquarium of 60 liters is sufficient. For larger species such as Austrolebias elongatus, at least 100 liters should be provided. After raising them together, it is possible to keep larger animals like Rachovia species together in a 60-liter aquarium. However, if an animal is removed, meaning the hierarchy within the group changes, the entire order can collapse. The animals must be quickly separated if we do not want to lose a large part of the fish.

There were early indications of considerable aggression in SAA males (Adloff, 1923a). In the aquarium, I observed the males selecting a preferred spawning site stationary and defending it consistently against rivals. Regularly, a male stands over the introduced containers with spawning substrate. However, females are not timid either. The setup is important for the expected interactions. For hygienic reasons and for simplification, bottomless tanks are often only equipped with a bowl full of peat. If the fish react to reflections, a thin layer of sand or peat helps.

For feeding, I prefer live food, as it distributes itself in the tank and is thus accessible to all present animals. Moreover, it puts less strain on the water if it is quickly eaten. With frozen food, I often find more frequent feedings useful solely due to the water strain. Additionally, we must pay attention to fish that do not get to the food as easily. Ultimately, it may be beneficial to temporarily separate them from the stronger animals. To remember: feeding strains the water, which we can counteract with frequent water changes.

Temperature

Temperature plays a role in our South American annual Killifish in multiple ways. Water temperature influences all life processes in these poikilothermic animals. And during the incubation of the eggs, it is a factor that affects the duration of the developmental time. With temperatures between 22 and 26°C, we will not experience any unpleasant surprises.

It is often recommended to keep the animals cooler to extend their lifespan.

Liu & Walford (1969) showed that one-year-old fish of Austrolebias bellottii have a longer life expectancy when they are primarily kept in water at 15°C compared to 20°C during their lives. The longer life expectancy was accompanied by changes in the ratio of soluble to insoluble collagen. These studies say nothing about behavior or spawning behavior. From experience, I would claim that productivity suffers. In aquaristics, we are particularly concerned with the reproduction rate. Among South American substrate spawners, a portion of the eggs usually dies during the incubation period. Therefore, we create favorable conditions when we provide the species with optimal conditions and pay attention to a high number of eggs in the spawn. I can therefore only advise against keeping them too cool. However, a cooler upbringing of Austrolebias bellottii is sensible so that the animals develop their brilliant blue coloration. Once the fish are fully grown, we increase the temperature again. Partially, a cooler storage of the eggs is already recommended with regard to coloration, which I have not followed.

Nutrition for Cynolebias & Co.

South American annual Killifish have adapted over long periods to their habitats. Since it is always an adaptation to seasonal waters, the fluctuating water level until the drying up of the water bodies raises the question of what types of food can be expected under these special conditions. The food supply varies throughout the year. Fish adapt to these changes. Looking at the few research findings on the nutrition of our South American annual Killifish, we get rough guidelines for sensible feeding. In the natural occurrence areas, the availability of food organisms fluctuates in quantity and types with the course of the year. This fundamentally speaks for a varied diet. Rachovia and Austrofundulus are said to accept dry food, which I have not yet tried.

In principle, it has been known since the observations of Boschi (1957) that all South American annual Killifish should always have food available. Otherwise, they lose body substance within a very short time. For adults, this naturally affects productivity, and for juveniles, it hinders rapid growth. Many species from Venezuela require substantial food. This is supported by several reports. Thomerson, J.E. & Taphorn, D.C. (1987) mention for Austrofundulus limnaeus from the Maracaibo Basin (Venezuela) the main components of food in descending order of their significance: 55% fish, small crustaceans, beetles, and red mosquito larvae. As an example of the rapid depletion of body substance, the report by Thomerson, J.E. & Taphorn, D.C. (1987) can also serve. Thomerson & Hoigne found large adult Austrolebias limnaeus at the brink of death in a puddle with knee-deep water and abundant aquatic vegetation. There, hundreds of emaciated bodies floated on the surface. They were just a bit more than "skin and bones." In the aquarium, fed with beef heart, many animals recovered and lived for over a year after collection.

In the natural diet of our South American annual Killifish, there were also beetles, red mosquito larvae, small crustaceans, or ants. Lilyestrom & Taphorn (after Thomerson, J.E. & Taphorn, D.C. (1987)) reported that an adult male of Rachovia hummelincki in 15 minutes consumed 135 Aedes aegypti of the fourth developmental stage of these mosquito larvae. In the first description of Austrofundulus myersi , Dahl (1958) mentions that the species feeds on aquatic insects, particularly mosquito larvae. Small Poecilia caucana were also captured. When food becomes scarce, relatively large prey (small females of Rachovia splendens) are attacked. In the area of occurrence, the species can be attracted with beef liver or muscle meat. Surprisingly, they do not readily eat this food in the aquarium. In studies on Austrolebias and Cynopoecilus , zooplankton formed the main part of the diet. This was followed by eggs, algae, diatoms, and insects, followed by red and black mosquito larvae, among others (Laufer et al. 2009).

A varied diet includes frozen and live red and black mosquito larvae, enchytrae, grindal, Drosophila , and earthworms. The majority of South American annual Killifish tolerate fatty food well based on my experiences. Today, I also feed Tubifex again, as earlier problems have not occurred again (keyword "Fräskopfwurm").

Literature

- Adloff, A. (1923a): News from Cynolebias adloffi Ahl. Blätter 34(1): 1 - 3.

- Adloff, A. (1923b): Letter from Brazil. News from Cynolebias et al. Blätter 34(12): 251 - 252.

- Barois, Nibia et al. (2016): Annual Fishes. Life History Strategy, Diversity, and Evolution. - CRC Press - Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742.

- Bela, Heinz (1982): Cynolebias constanciae Myers, 1942. DKG-J. 14(7): 104-106.

- Belote, D. F. & Costa, W. J. E. M. (2002): Reproductive behavior patterns in the neotropical annual fish genus Simpsonichthys Carvalho, 1959 (Cyprinodontiformes, Rivulidae): Description and phylogenetic implications. - Bol. Mus. Nac. 489: 1-10.

- Belote, D. F. & Costa, W. J. E. M. (2003): Reproductive behavior of the Brazilian annual fish Cynolebias albipunctatus Costa & Brasil, 1991 (Teleostei, Cyprinodontiformes, Rivulidae) a new report of sound production in fishes. - Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro 61(4):.241-244.

- Berg, Carlos (1897): Contributions to the knowledge of South American fish, especially those of the Republic of Argentina. An. Mus. Nac. de Buenos Aires V: 263-302. (not viewed)

- Boschi, Enrique (1957): Argentine pearl fish. - T. F.H. Publ. Inc., Jersey City, N. J., 23 pages.

- Brüning, Christian (1912): Pocket calendar for aquarium enthusiasts. - Gustav Wenzel & Sohn, Braunschweig. 96 pages.

- Brüning, Christian (1913): Pocket calendar for aquarium enthusiasts. - Gustav Wenzel & Sohn, Braunschweig. 122 pages.

- Brüning, Christian (1914): Pocket calendar for aquarium enthusiasts. - Gustav Wenzel & Sohn, Braunschweig. 133 pages.

- Calviño, Pablo A., Alonso, Felipe & de Torres, Jorge Sanjuán (2007): Filling of gas in the swim bladder of post-larvae of South American annual fish (Cyprinodontiformes; Rivulidae). - Boletín del Killi Club Argentino BIBKCA No. 13: 18-39.

- Cauvet, Christian (2011): Patience and length of time. An incubation experiment of annual killifish eggs with Simpsonichthys magnificus. - KR 1/2011: 14-20.

- Costa, W. J. E. M. (1990a): Phylogenetic analysis of the family Rivulidae (Cyprinodontiformes, Aplocheiloidei). - Rev. Brasil. Biol. 50(1): 65-82.

- Costa, W. J. E. M. (1990b): Classification and distribution of the family Rivulidae (Cyprinodontiformes, Aplocheiloidei). - Rev. Brasil. Biol. 50(1): 83-89.

- Costa, W. J. E. M. (1995): Revision of the neotropical annual fish genus Campellolebias (Cyprinodontiformes: Rivulidae), with notes on phylogeny and biogeography of the Cynopoecilina. - Cymbium 19: 349-369

- Costa, W. J. E. M. (2011): Comparative morphology, phylogenetic relationships, and historical biogeography of plesiolebiasine seasonal killifishes (Teleostei: Cyprinodontiformes: Rivulidae). - Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2011(162): 131–148.

- Costa, W. J. E. M. (2011b): Hypsolebias nudiorbitatus, a new seasonal killifish from the Caatinga of northeastern Brazil, Itapicuru River basin (Cyprinodontiformes: Rivulidae). - IEF 22(3): 221-226.

- Costa, W.J.E.M. (2012a): Diversity and conservation of killifishes of the Brazilian Caatinga. - Killi-News Nr. 549: 73-82.

- Costa, W.J.E.M. (2012b): Delimiting priorities while biodiversity is lost: Rio’s seasonal killifishes on the edge of survival. - Biodivers Conserv 21:2443–2452.

- Costa, Wilson J. E. M.; Pedro F. Amorim and Giulia N. Aranha (2014): Species limits and DNA barcodes in Nematolebias, a genus of seasonal killifishes threatened with extinction from the Atlantic Forest of southeastern Brazil, with description of a new species (Teleostei: Rivulidae). - Ichthyol. Explor. Freshwaters 24(3): 225-236.

- Wilson J. E. M. Costa (2014): Six new species of seasonal killifishes of the genus Cynolebias from the São Francisco river basin Brazilian Caatinga, with notes on C. porosus (Cyprinodontiformes: Rivulidae). - Ichthyol. Explor. Freshwaters 25(1): 79-96.

- Dahl, George (1958): Two new annual cyprinodont fishes from northern Colombia. - Stanford ichthyological bulletin 7(3): 42-46.

- Costa, Wilson J.E.M., Amorim, Pedro F. & Mattos, José Leonardo O (2018): Diversity and conservation of seasonal killifishes of the Hypsolebias fulminantis complex from a Caatinga semiarid upland plateau, São Francisco River basin, northeastern Brazil (Cyprinodontiformes, Aplocheilidae). - Zoosyst. Evol. 94 (2) 2018, 495–504.

- Eigenmann, Carl H. (1907): The poeciliid fishes of Rio Grande do Sul and the La Plata basin. - Proc. US Nat. Mus. 32(1532): 425-433.

- de Greef, Jaap-Jan (1993): Bellysliders: A problem or not. AguaTropica 2(3): 3-4, 1993

- Hagenmaier, Hans E. (1995): The enzymatic hatching of fish. pp. 101-113 in: Reproductive biology of aquarium fish. Birgit Schmettkamp Verlag.

- Foersch, W. (1956a). Care and breeding of Cynolebias nigripinnis. DATZ 9(2): 35-39.

- Foersch, W. (1956b): Observations on the behavior and egg development of substrate-spawning fish. - Z. für Vivaristik 2: 8–13, 39–45, 113–117, 177–184.

- Foersch, W. (1958): Observations and experiences in the care and breeding of Cynolebias ladigesi Myers. - DATZ 11(9): 257-260

- Foersch, Walter (1961): Cynolebias (Cynopoecilus) ladigesi. - Tropical Fish 1(9): 396-404.

- Foersch, Walter (1975): The "fighting gaucho" dances around his female. Breeding and care of Cynolebias ladigesi and melanotaenia. AM 9(10): 404 – 409.

- Foersch, Walter (1978): How does the elongated fan fish spawn? Observations on the care and breeding of Cynolebias elongatus. - AM 12(2): 86-93.

- Fröhlich, Fritz (1972): Some observations on the breeding of Cynolebias species. - DKG-J. 4(1): 1-4.

- Garcez, Daiana K.; Barbosa, Crislaine; Loureiro, Marcelo; Volcan, Matheus V.; Loebmann, Daniel; Quintela, Fernando M. & Robe, Lizandra J. (2018): Phylogeography of the critically endangered neotropical annual fish, Austrolebias wolterstorffi (Cyprinodontiformes: Aplocheilidae): genetic and morphometric evidence of a new species complex. - Environ Biol Fish.

- García, Daniel; Loureiro, Marcelo & Tassino Bettina (2008): Reproductive behavior in the annual fish Austrolebias reicherti Loureiro & García 2004 (Cyprinodontiformes: Rivulidae). - Neotropical Ichthyology, 6(2):243-248.

- Johannis, M. & Köpp, C. (2015): Fish that fell from the sky. - Amazonas11(6 No. 62): 14-22.

- Langton, Roger W. (1979): A Numbering System to Indicate Peat Moss Wetness. - JAKA 12(6): 187-188. Reprint 1989 in JAKA 22(6) 193-194.

- Laufer, Gabriel et al. (2009): Diet of four annual killifishes: an intra and interspecific comparison. - Neotropical Ichthyology 7(1):77-86.

- Liu & Walford: Laboratory Studies on Life-span, Growth, Aging, and Pathology of the

- 1969] Annual Fish, Cynobelias bellottii Steindacher 7

- Loureiro, Marcelo; Sá, Rafael de 2; Serra, Sebastián W.; Alonso, Felipe; Lanés, Luis Esteban Krause; Volcan, Matheus Vieira; Calviño, Pablo; Nielsen, Dalton; Duarte, Alejandro; Garcia, Graciela (2018): Review of the family Rivulidae (Cyprinodontiformes, Aplocheiloidei) and a molecular and morphological phylogeny of the annual fish genus Austrolebias Costa 1998. - Neotropical Ichthyology, 16(3): e180007:1-20.

- Meder, Dr. E. (1953a): Cynolebias bellottii Steindachner. - DATZ 6(7): 169 - 172.

- Meder, Dr. E. (1953b): Cynolebias bellottii Steindachner (considering Cynolebias nigripinnis Regan). DATZ 6(8): 197 - 201.

- Nascimento, WS, Yamamoto, ME.b, Chellappa, NT.c, Rocha, O.d and Chellappa, S. (2015): Conservation status of an endangered annual fish Hypsolebias antenori (Rivulidae) from Northeastern Brazil. - Braz. J. Biol. 75(2): 484-490.

- Nielsen, Dalton (2000): Saving the Killies of Brazil. - KR 05/200 November 2000: 16-19.

- Nielsen, Dalton T. B. & Brousseau, Roger (2014): Description of a new annual fish, Papiliolebias ashleyae (Cyprinodontiformes: Rivulidae) from the upper Rio Mamoré basin, Bolivia. - aqua, International Journal of Ichthyology 20(1): 53-59.

- Nieuwenhuizen, A.v.d. (1977): Cynolebias alexandri. DATZ 30(11): 364 – 369.

- Ott, Dieter (1996): Cynolebias affinis or: How do I breed Annual Killifish? - Agua tropica2 1(6): 5-7.

- Ott, Dieter (2020): Fascination Aphyos - Successfully keeping and breeding ornamental killifish. - VerlagsKG Wolf, 272 pages.

- Peters, N. (1963): Embryonic adaptations of oviparous cyprinodonts from periodically drying waters. - Int. Rev. ges. Hydrohiol., 48: 257-313.

- Pillet, Didier (2008): Brazilian walks. Observations and measurements in the temporary ponds of the Cerrado and Brazilian coast. - KR 03/2008 May/June 2008: 5-15.

- Pillet, Didier (2013): Tips for successfully handling annual fish eggs. - KR 1/2013: 17-22.

- Rachow, (1912): Is Cynolebias maculatus Steind. the female of Cynolebias bellottii Steind.? – Blätter 23(52): 835-838.

- Regan, C. Tate (1912a): A Revision of the Poeciliid Fishes of the Genus Rivulus, Pterolebias and Cynolebias. - Ann. And Mag. Of Natural History 8(10): 494.

- Regan, C. Tate (1912b): Sexual differences in the Pocciliid Fishes of the Genus Cynolebias. - Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 10: 641-642.

- Rosskopf, Christian (2004): Clay as spawning substrate for South American substrate spawners. - DKG-J. 36(5): 131 -139.

- Schwarz, Rich. (1918): Cynolebias belotti Steindachner. - Wochenschrift 15(3): 19-21.

- Siegel, G. (1958): Interesting news about substrate-spawning South American cyprinodonts. - DATZ 11(7): 200-202.

- Seegers, Lothar (1979): Cynolebias bellottii: Historically, scientifically and aquaristically considered. - aquarium magazine 13(2): 78-83.

- Seegers, Lothar (1980): Cynolebias alexandri and some observations on the existence of Cynolebias gibberosus. - DA October 1980 No. 136: 506-513.

- Seegers, Lothar (2000a): Campellolebias – killifish with internal fertilization. - Aquarium today 18(3): 584-587.

- Seegers, Lothar (2000b): Fan fish from South America. - AF 32(2 No. 152): 30-34.

- Siegel, G. (1958): Interesting news about substrate-spawning South American cyprinodonts. - DATZ11(7): 200-202.

- Stansch, K. (1914): The exotic ornamental fish in word and image. - Verlag Vereinigte Zierfischzuchtstätten Rahnsdorfer Mühle near Berlin. 349 pages.

- Steinberg, Christian (2011) The brackish water killifish, Fundulus heteroclitus – model for epigenetics and evolution. - AF 43(1 No. 217): 62-66.

- Steindachner,76. Arch. Soco Biol. Montevideo, 26: 44-49.- 19Mb. Three new species of the genus Cynolebias STEINDACHNEI1l8, 76 (Teleostomi, Cyprinodontidae). Como Zool. Mus. Hist. Nat. Montevideo, 8: (I02'): 1-36, 6 pIs.

- Thomas, Karl (1938): All sorts of interesting things from Cynolebias bellotti. - W30(34): 537-539.

- Thomerson, Jim & Taphorn, Don (1992): The annual killifishes of Venezuela. Part 1: Maracaibo basin and coastal plain species. - TFH 41(1): 71-96

- Vaz Ferreira, R., Sierra, B. & Scaglia de Paulete, S. S. (1963): Hatching and

- subterranean retrograde propulsion of postlarvae of Cynolebias (Pisces, Cyprinodontidae) Neotrópica 9 (30), 111-112 – not viewed.

- Wildekamp, R. H. (1995): A world of killies. Atlas of the oviparous cyprinodontiform fishes of the world.

- Volume 2. – American Killifish Association, Mishawaka, Ind., 384 p.

- worldfish wiki (2025): https://www.wf-wiki.de/index.php?title=Cynolebiidae accessed 2025).

- Wourms, J. P. (1964): Comparative observations on the early embryology of Nothobranchius taeniopygus (Hilgendorf) and Aplocheilichthys pumilis (Boulenger) with special reference to the problem of naturally occurring embryonic diapause in teleost fishes. – In: East African Freshwater Fisheries Research Organization, Annual Report for 1964, Jinja, 68–73.

- Wourms, J. P. (1972): Developmental biology of annual fishes. III: Pre-embryonic and embryonic diapause of variable duration in the eggs of annual fishes. – JEZ 182 (3): 389–414.