Step into the world of the Amazon, a river that is synonymous with endless wilderness and incredible biodiversity. This gigantic waterway, renowned for its length and volume of water, is home to countless species, including many popular aquarium fish.

The Amazon is a term in itself. The Amazon is the home of the majority of the fish we keep. With a length of approximately 7,000 km, it is considered the longest river in the world. Its basin covers an area of more than 7 million km². In its basin, we find more than 1,100 large rivers, of which 15 are even longer than 2,000 km. For comparison, the Vltava would fit into one of these rivers almost five times, and nearly 16 times into the Amazon itself. Almost half of the basin is located in Brazil. The rest is divided among Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, and even a small part remains in Guyana.

Among the largest sources of the Amazon are the Rio Ucayali and the Rio Marañón. Essentially, they lie next to each other and derive from the geologically young Andes. Both of these rivers then merge in Peru near the town of Nauta. At the borders of Brazil and Colombia, this river has two names; in Peru, it is already called the Rio Amazonas, while for Brazilians, this river is named Rio Solimões until it merges with the Rio Negro. Only after this well-known "encontro das águas – the confluence of rivers" do Brazilians come to their senses and finally call the Amazon the Amazon. Not far from this confluence lies the million-strong city of Manaus, which has been recognized by many Czech aquarists as the starting point of their aquarium adventures in the Amazon rainforest.

Even the aforementioned tributaries have created their own basins with countless tributaries. The Madeira basin constitutes about 20% of the total area of the Amazon basin, the Rio Tapajós basin occupies about 7.1%, and the Rio Xingu 7.3% in the southern direction, while the northern basin is clearly dominated by the basins of the rivers Negro and Branco with 10%. Although it is almost unimaginable, the water level here can fluctuate by as much as 13 meters depending on whether it is or is not the rainy season. The northern tributaries of the Amazon have significantly more water from March to the transition of January/February, while the southern tributaries have more from November to the transition of March/April.

Every day, an unimaginably large amount of water flows towards the Atlantic through the Amazon. The depth does not exceed 120 m. From the rainforest city of Iquitos in Peru to the mouth in Brazil near the city of Belém, you would measure an impressive 3,700 km in length, but the height difference along the entire length is only just under 100 m. The narrowest part of the river can be found at Obidos, where it measures barely 2 km; at low water levels, it has even been measured at only 1,600 m, while at its widest point, the Amazon averages 10 km, and during the rainy season, this area can triple. Another surprising figure is that 200,000 m³ of water flows through the Amazon per second. That is what I call flow! Such a volume of water also carries with it a corresponding amount of materials and sediments. Every day, nearly 3 million tons of soil, rocks, and various debris are washed into the water. Even here, the annual figure is certainly astonishing, as nearly 800 million tons of sediments reach the mouth of the river. The delta of the Amazon itself measures more than 250 km in width.

Some scientists divide the Amazon basin into 3 parts:

1) The Upper Amazon runs from the sources in the Andes to the mouth of the Rio Tefé in Brazil.

2) The Middle Amazon is the area from Tefé to the town of Santarém at the mouth of the Rio Tapajós and

3) the Lower Amazon is the section from Santarém to the mouth of the Amazon delta into the Atlantic.

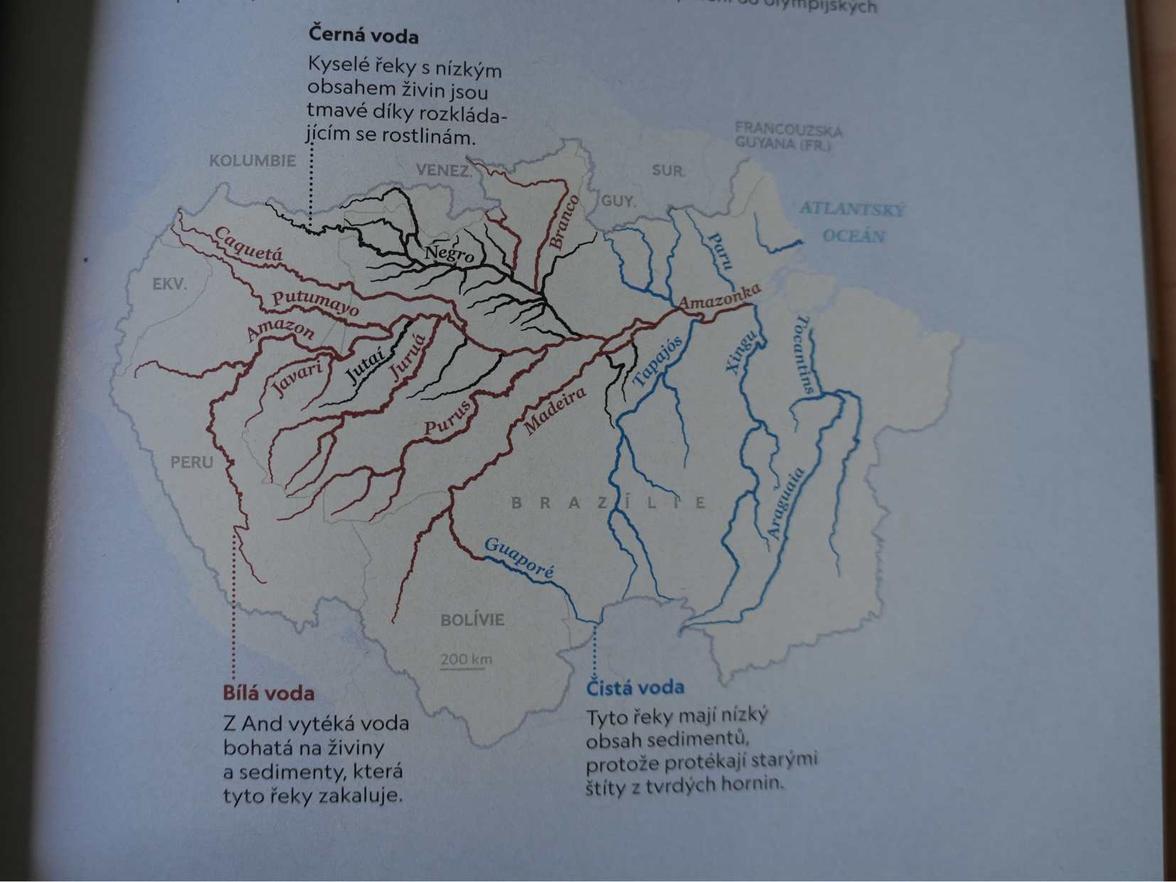

Division by water type

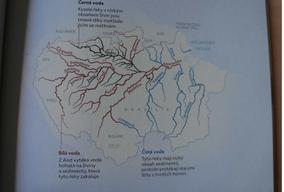

In their contexts, there is often talk of different types and species of water. The most well-known is the division into 3 basic types, which was introduced in the last century by Prof. Harald SIOLI (1910-2004), the father of limnological research in the Amazon. He began his work here in 1945. Since then, his work has been repeatedly published. We will, of course, adhere to his classification, which is generally recognized and valid.

Black water

First, we look at the so-called black waters. This type of water is represented by olive to coffee-colored streams with more or less clear water. This coloration is usually due to decomposing humic substances (natural organic materials formed from the decomposition of mainly plant debris). Humic substances are only slowly subject to further decomposition and are found in large quantities in soil, peat, coal, and some waters. Depending on their solubility, they are divided into humins, humic acids, and fulvic acids. Most of these waters originate from flat areas, where caatinga occurs, which is a vegetation of shorter trees formed amidst rainforests either due to the influence of dry permeable soils and local dry climates or due to extremely high rainfall and leached nutrient-poor soils, or campo, which are grassy areas in the interior of Brazil, formed in the vicinity of caatinga formations and rainforests on long-term waterlogged or long-term dried soils. Due to artificially established fires and deforestation, the area of campos is continually increasing. Campos can be considered tropical steppes or savannas. During the rainy season, nothing prevents the water from spreading around and flooding large areas. Brazilians call such areas "Igapó".

Visibility here reaches from one to a maximum of three meters. The streams of central Amazonia with black water are very poor in decomposed inorganic substances and their other typical feature is also low pH, ranging from 3.5 to 4.9. Electrical conductivity here does not exceed 6 µS/cm. However, if you think that everywhere where plant debris enters the river, black-type waters occur, you are deeply mistaken. Looking at these rivers through the eyes of a hunter, we find a relatively large representation of individual species, but in terms of quantity, these rivers are often referred to as "rios do faminto" – the so-called starving rivers. The fish living here are heavily dependent on food intake from other sources (e.g., insects, flowers, fruits). A classic example here would be the Rio Negro, which, especially after merging with the Rio Branco in its lower section, no longer meets the designation of a starving river.

White water

White water is the second type in the order we will focus on now. It is rich in sediment, the color is somewhat murky, and resembles coffee with milk. Most of these waters originate in the eastern Andes. Although most of this area is covered by mountain rainforest, abundant, regular, and heavy rainfall leads to intense erosion.

The bedrock originates from geologically young areas, rocky and sediment-rich formations easily enter the waters, and sediments slowly dissolve in the waters, enriching them. Where they settle, they are usually slow and calm-flowing streams, creating soils with dense vegetation, known as "Varzeas." The Amazon acts here as a large self-replenishing machine, as the erosion of its own riverbed significantly contributes to enriching its flows with minerals.

Visibility here drops to 10 – a maximum of 50 cm. The pH value is usually around neutral pH 6.2-7.2. Electrical conductivity here reaches 30–70 µS/cm. Unlike starving rivers, these rivers are full of life. Here we also find large representatives of tetras or catfish, which, however, usually do not end up in our tanks, but on the tables and in the stomachs of local natives. Their typical representatives are the Amazon itself, the Rio Branco, or the Rio Madeira.

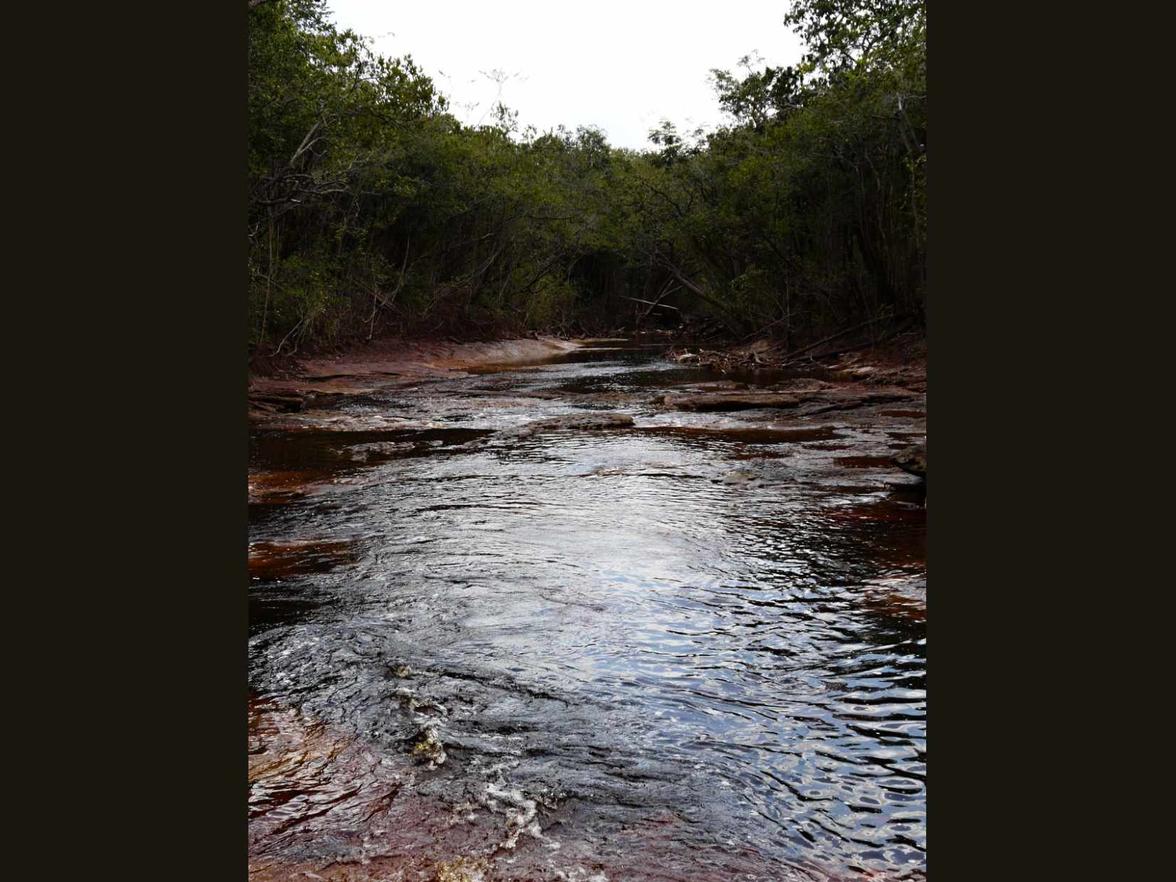

Clear water

The last type we will look at today is the so-called clear water. Rivers of this type are also associated more with flat areas; their sources would most likely be found in ancient mountain ranges of Guyana and central Brazil, which are no longer able to supply their waters with sediments. These clear waters are often slightly colored, their water color evokes a visit to the Mediterranean area – yellowish to olive green, clear water is excellently transparent and visibility here can reach 4.5 meters. The pH value of these waters can vary significantly, sometimes reaching 4.5, but its values can also reach 6.6. Where the substrate consists of limestones, the pH value can rise to 7.8. Electrical conductivity here is usually in lower values, around 20 µS/cm, but values between 8–12 µS/cm are not uncommon. The Rio Xingu, Tocantins, or Tapajós in southeastern Amazonia are basic examples of rivers with clear water.

Other types of water

However, if you think that only these and no other types can be found in the Amazon, you are very mistaken. Everywhere where waters flow into further, stronger streams, there is mixing. Also, during dry and rainy seasons, incoming waters can mix with the original composition, thus preparing unpleasant surprises for the inhabitants.

As you will surely agree, not all the factors listed here can be learned by a fish keeper. Often, they only find out which type of river their fish comes from, and even that is often not enough. Ideally, it would be to know the exact chemical composition of the water from the fish's habitat, to know which factors still influence it and which do not. Therefore, it is not surprising that even sometimes guaranteed "recipes" for water treatment do not work.

|

Type of water |

Coloration and visibility |

Sources |

Vegetation |

Example |

pH value |

|

Black waters |

Olive, coffee brown, clear; |

Amazon basin |

Caatinga, campo |

Rio Negro, Arapiuns, Tefé |

3.7-4.9 |

|

White waters |

Yellowish, murky; |

Andes, Serra Parima |

Andean mountain rainforest |

Solimões, Amazon, Madeira |

6.2-7.2 |

|

Clear waters |

Yellow, olive green, clear; |

Highlands of central Brazil, Guyana |

Amazon rainforest |

Xingu, Tapajós, Tocantins |

4.5-7.8 |

Images:

- From the peaks of the Andes, you can easily observe Mount Mismi, where some of the sources of the Amazon are located. Here originates the Apurímac (730.7 km), which later changes its name to Ene (180.6 km) and then Tambo (158.5 km).

- The Rio Urubamba originates under the name Vilcanota in the Central Andes southeast of Cuzco near Puna. In the Sacred Valley between Pisac and Ollantaytambo, it is sometimes also called Wilcamayu (the sacred river). It flows through deep canyons that separate the ridges of Vilcabamba and Vilcanota, merging with the Tambo-Ene-Apurímac river and forming the Ucayali river.

- In the residual waters of the Rio Negro, many fish species find refuge during the dry season.

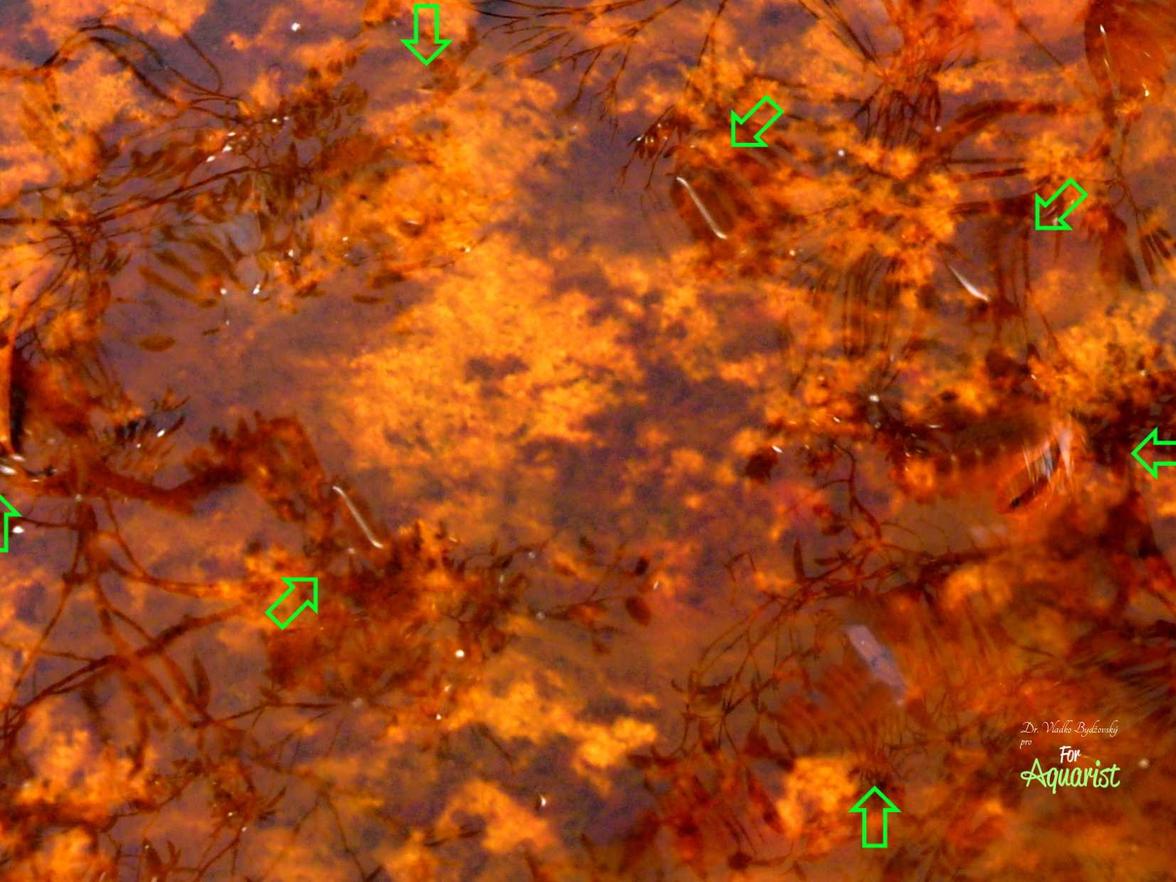

- In small streams with mostly stagnant or only slowly flowing water, in the riparian zones that are only about 20 cm deep, the red neon tetras Paracheirodon axelrodi live.

- In similar tributaries, we caught interesting cichlids Crenicichla regani.

- The red neon tetras Paracheirodon axelrodi can be easily observed with the naked eye if we stand still on the shore for a moment. However, as soon as we move a little, we see only black water. The numerous cichlids that live here also disappear.

- Black piranhas are abundantly caught in the black waters of the Rio Negro above Manaus.

- Near Manaus, beautiful discus fish Symphysodon discus are also caught.

- Around Manaus, there are several different "red-bellied" variants of angelfish Pterophyllum scalare known as "Santa Isabel." They are sometimes also referred to as "Red Altum."

- Occasionally, we also encounter "freshwater dolphins" or the Amazon river dolphins Inia geoffrensis. These mammals can grow to 2-3 m in the case of males, and encountering them is an unforgettable experience that you will remember for the rest of your life.

- In similar locations with clear water, many turtles live. The prototype is the Rio Xingu.

- In these tributaries with clear water, we mainly caught tetras and cichlids.

- We catch large numbers of fish under the branches of riparian vegetation.

- Clear waters usually have a pH of 4.5-7.8 with visibility of 1-4.5 m. The most well-known are the Tapajós, Tocantins, and Xingu.

- In the vicinity of Manaus, you can easily rent a boat with the owner's whole family. They will take you wherever you want.

- The world-famous confluence of the black Rio Negro and the white Solimões near Manaus, after which the river is called the Amazon.

- The sharp boundary between black and white waters at the confluence of rivers near Manaus stretches for a full 7 km.

- The Amazon near Manaus has a depth of up to 175 m, which is why large cargo ships also sail here.

- The white sandy beach is typical for the Rio Negro.