Killifish are often seen as beautiful but difficult fish, suitable only for specialists. But is that really true? This article shows that even beginners can find species among them that bring joy to the hobby – without frustration or unnecessary myths.

Killifish are a highly diverse group – both in terms of life strategies (with species living in stable or seasonal, drying habitats, in both still and flowing waters) and in their appearance and coloration.

Most aquarists, when they hear the name, tend to think something like this: beautiful fish, but extremely difficult to care for, suitable only for specialists, aggressive, live just a few months, breeding is very complicated – in other words: not for me…

At this point, you might expect a passionate defense of Killifish from someone who has been working with them for over 20 years, and a thorough debunking of all these half-truths. But that’s not what this article will be.

It has to be said honestly: yes – there are Killifish species that are demanding to keep, that require a special approach, and for many of them, even with proper care, it’s common to end up with just a few fry. But that’s no different from other groups like tetras, cichlids, labyrinth fish, and so on – every group has species that are simply not suited for beginners.

At the same time, however, there are species that are perfectly suitable for newcomers – and these are the ones I’d like to focus on here.

I’ll take three sample questions from imaginary hobbyists interested in Killifish and try to show that not everything commonly said about them is necessarily true (and I ask experienced readers to forgive a few simplifications made in the interest of readability).

1) I have a small aquarium with dwarf fish – pearl danios and neon tetras. Would Killifish fit in there too?

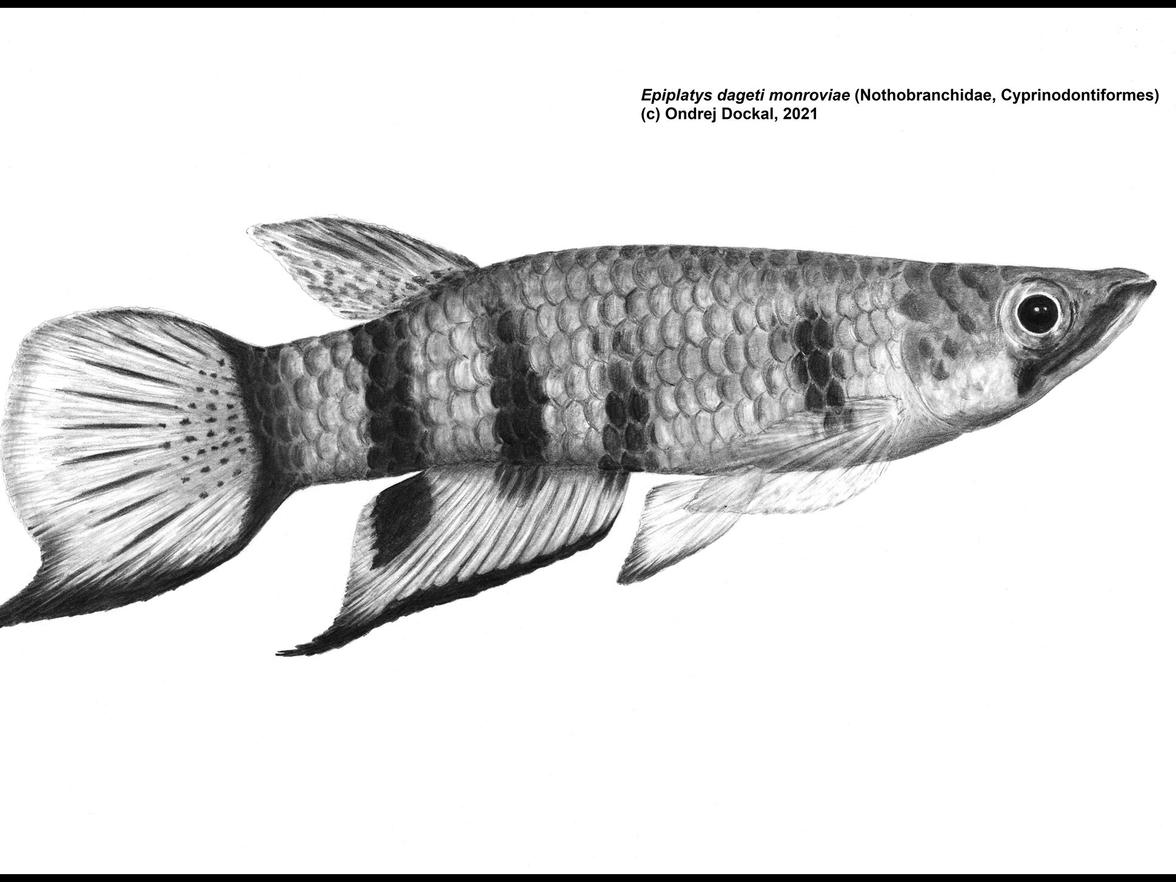

Yes – BUT you need to choose among the smallest and most peaceful species. A great example is Epiplatys annulatus.

From a care perspective, this species is quite undemanding when it comes to water parameters – it tolerates both soft and moderately hard water with a pH around 7. For breeding, however, softer water with a slightly acidic pH (below 7) is recommended. It readily accepts small live food, frozen food, and even high-quality dry food.

When it comes to breeding, keep in mind that the fry are extremely small. They hatch after about 2–3 weeks and require very fine live foods such as infusoria or rotifers. Early growth is fairly slow.

That said, successful breeding is also possible without intensive care – if the breeding tank is densely planted (Java moss and floating plants like duckweed are ideal), some of the eggs and fry can hide from adult fish and find natural food among the plants. In such a setup, it's possible to raise a few young even in a community tank with the parents.

Photo 1: Epiplatys annulatus – Fish of the genus Epiplatys (as well as Aphyosemion, Fundulopanchax, Aplocheilus, etc.) are excellent jumpers, so aquariums should always be securely covered.

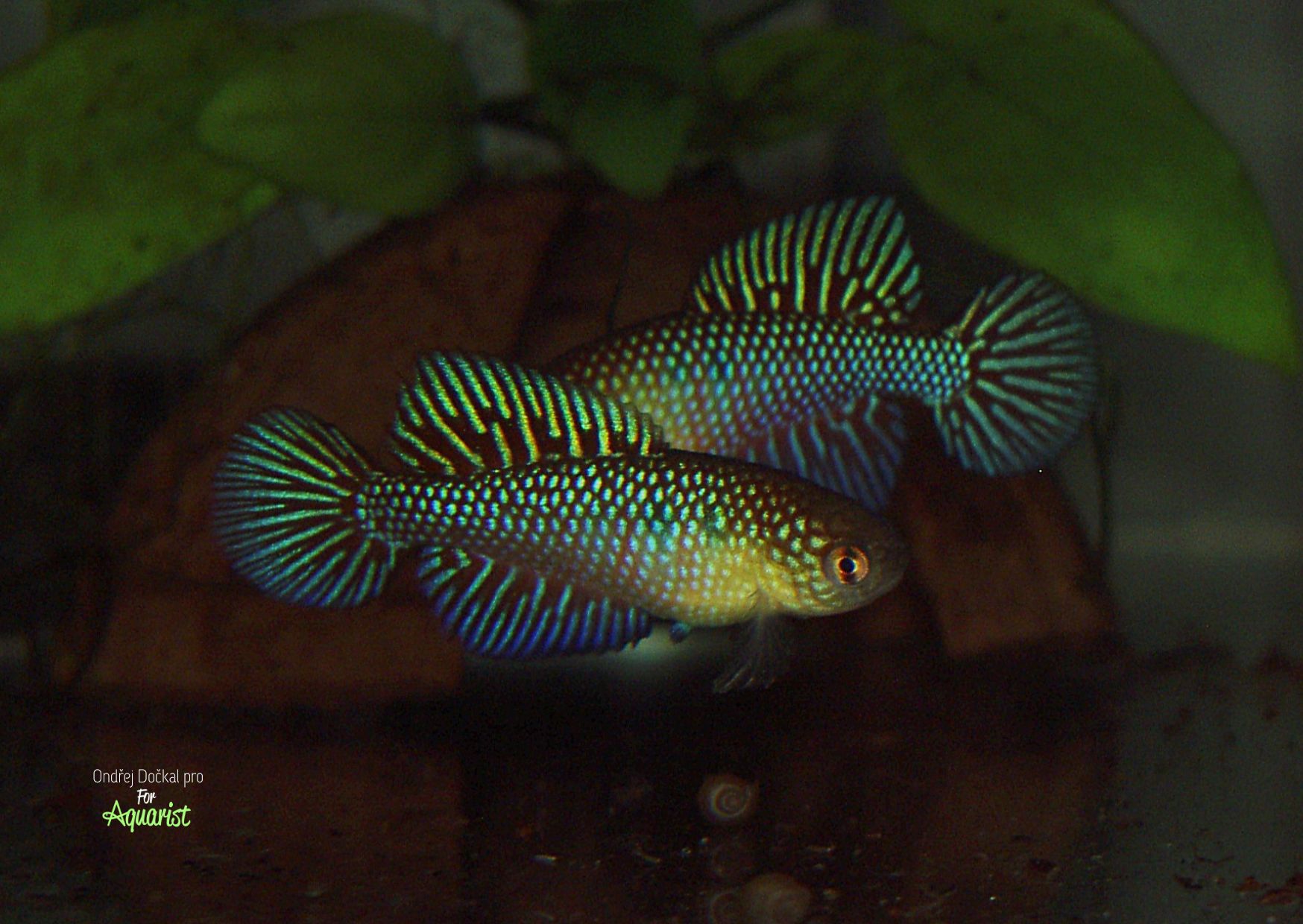

2) I have a standard aquarium with a typical mix of fish (tetras, barbs, platy fish, catfish…) – can I consider adding Killifish?

Yes – BUT again, it’s important to choose the right species. Killifish are quite lively by nature, so they’re not the best match for fish with long, flowing fins, which may provoke fin-nipping behavior. (For that matter, even tiger barb don’t mix well with veil-tailed guppies.)

These aquariums are suitable for hardy, easy-to-keep species from the genus Aphyosemion (e.g., striatum, gabunense, australe) or smaller representatives of the genus Epiplatys (such as dageti or chaperi).

From a feeding perspective, they’re undemanding – they enjoy live food but will also do well on frozen or even dry food. Soft water is only necessary during breeding.

The fry are usually of “standard” size, meaning they can be fed with fine Artemia nauplii. However, Epiplatys fry tend to be a bit smaller. Breeding is best carried out in a separate, small tank where a pair or trio (one male with two females) can be placed for a few hours (without feeding) or a few days (with feeding), along with sufficient spawning substrate like plant clumps or spawning mops.

The eggs hatch in about three weeks, and the fry grow quickly with good nutrition. Spawning in peat or lignocellulose can also be tried—after about two weeks of spawning, the substrate is lightly dried (so that it remains moist but does not drip water) and stored in a plastic bag or container. After another approximately three weeks (depending on the storage temperature—ideally 22–24 °C), the substrate is flooded with water.

Another option is the method described for E. annulatus – allowing the fry to grow in a densely planted tank with the parents, where some of the young may survive on their own.

Photo 2: Aphyosemion striatum – a species suitable for beginner Killifish keepers, with a lifespan of around 3 years. Photographed in a tank with Vietnamese cardinal tetras – peaceful cohabitation. (Photo: Zuzana Dočkalová)

Photo 3: Diapteron georgiae – all species in this genus prefer cooler water (optimal range: 18–22 °C). With proper care, they can live for over 4 years. However, breeding is more demanding. These species also require live or at least frozen food. They are stunning fish but suitable only for more experienced aquarists.

3) I have an empty aquarium in the hallway – it doesn’t get much heat or light… could I still try keeping something in it?

If the temperature hovers around 20 °C – dropping to about 15 °C in winter and rarely rising much above 22 °C in summer – that’s ideal for South American Killifish from the Austrolebias* group.

These are fish that typically grow to about 4–6 cm, with the largest species reaching up to 10–15 cm.

In terms of breeding, they are somewhat more demanding when it comes to food – they require rich live food, though in a pinch they can be acclimated to frozen foods (e.g., mosquito larvae). In tanks with at least some structure, group breeding (with three or more males and several females) is possible. In smaller, more open tanks, it’s better to keep just a pair or a trio.

For spawning, you’ll need to place a spawning container in the tank (such as a tall glass or a weighted plastic cup) filled with substrate – typically peat (important: use only 100% natural, fertilizer-free peat!) or lignocel (coconut fiber), where the fish will deposit their eggs.

After a few weeks, remove the substrate, gently squeeze out excess water, and store it in a sealed plastic bag or container, ideally in the shade at 20–24 °C. Depending on the species and storage conditions, the incubation time can vary from 2 to 6 months. After this period, the substrate is rehydrated with cooler water (around 16–18 °C). The first fry usually hatch within a few hours, with some exceptionally emerging the next day.

Due to the variability in incubation length, it’s worth rehydrating the substrate again after the first (or even second or third) attempt, checking for unhatched eggs, and continuing storage if needed.

Once hatched, the fry readily accept the smallest Artemia nauplii and grow quickly. An aquarium housing these species should include plants with low light requirements like Java moss or brown algae, both of which tolerate winter temperatures around 15 °C without issue.

Under optimal temperature conditions, these Killifish typically live for about 10–14 months. Some of the relatively easier species to keep and breed include Austrolebias* nigripinnis, Austrolebias* paucisquama, and Austrolebias* bellottii.

Note: There are many other annual Killifish species suitable for typical room temperatures – such as those from the genera Simpsonichthys, Hypsolebias, or Spectrolebias. However, keep in mind that some of these produce extremely tiny fry (e.g., Hypsolebias carlettoi or Notholebias minimus), which require extra care during the early stages of development.

Photo:

Photo 4: Austrolebias* nigripinnis – one of the best-known representatives of the genus, and a species well-suited for beginner Killifish breeders.

Photo 5: Austrolebias* arachan – a very rarely kept South American Killifish. Breeding is highly challenging: females lay only a few eggs, and a significant portion often fails to survive the incubation period.

Photo 6: Simpsonichthys santanae – a species suitable for beginner breeders, well adapted to standard room temperature conditions.

Photo 7: Hypsolebias fulminantis – a striking species suited only for experienced breeders, kept under typical room temperature conditions.

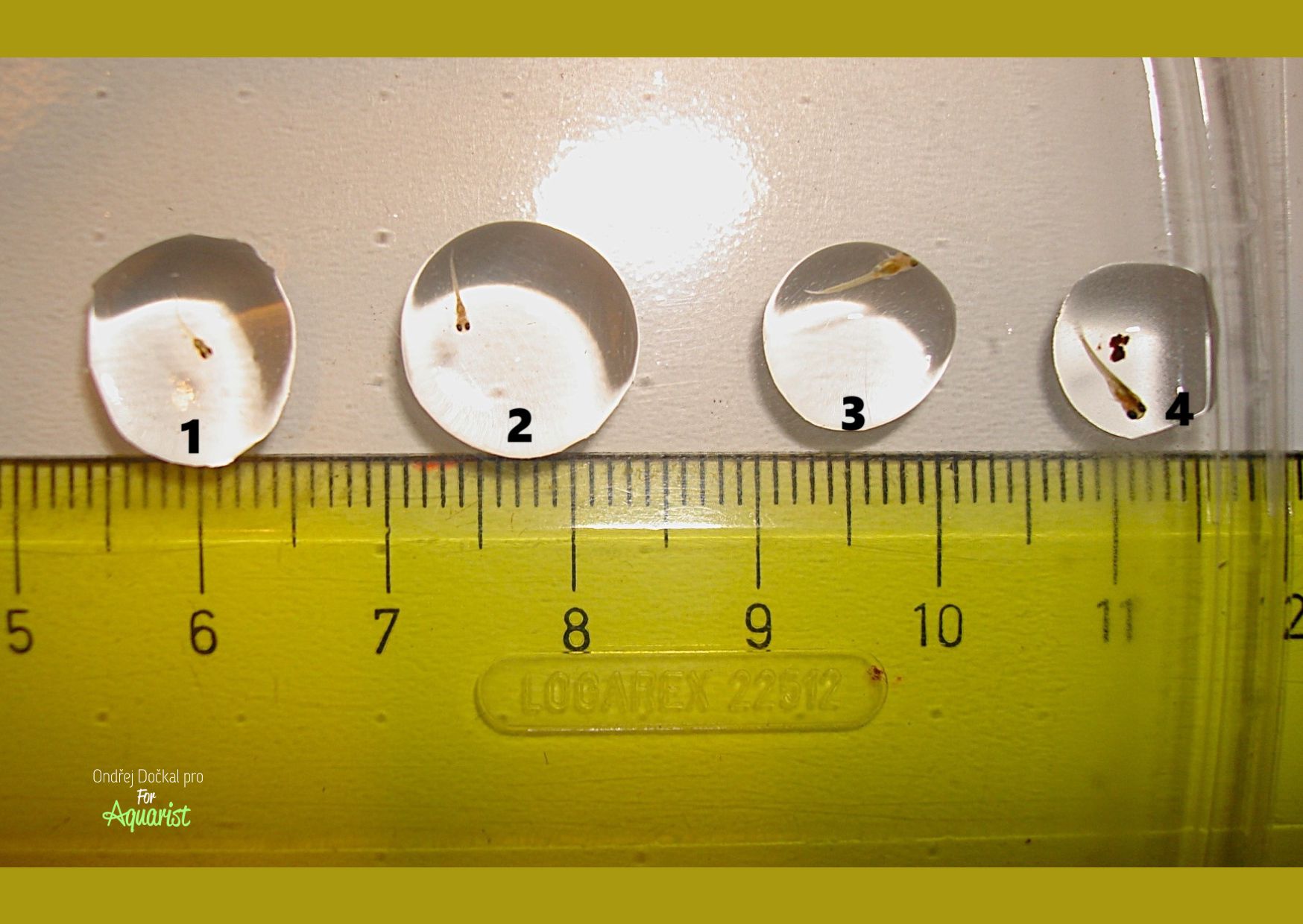

Photo 8: Size comparison of fry from different Killifish species (all are one-day-old except for no. 1): 1 – Epiplatys annulatus (4 days old), 2 – Hypsolebias fasciatus, 3 – Austrolebias* bellottii, 4 – Simpsonichthys boitonei.

What to add in conclusion?

This article was not intended to be a comprehensive guide to breeding Killifish. Rather, its goal was to show that there’s no reason to fear keeping or breeding these fascinating fish – certainly no more than with any other group.

As with any fish, it’s strongly recommended that anyone interested in breeding Killifish gathers as much information as possible beforehand – whether from books, online sources, or directly from experienced breeders who specialize in this unique group.

Where can you find such breeders?

In the Czech Republic, most Killifish enthusiasts and breeders are connected through the Czech Killifish Association - Česká halančíkářská společnost, which organizes an annual Killifish exhibition in Prague:

👉 https://www.halancici.cz

This event is attended not only by domestic breeders, but also by many international participants who regularly showcase their own fry. If this article has sparked your interest, I encourage you to mark your calendar for this year’s exhibition:

September 11–14, 2025.

*Note: The genus Austrolebias was revised by taxonomists in 2023, resulting in the establishment of several new genera. For clarity, the original genus name Austrolebias is used here with an asterisk. See also https://www.mna.gub.uy/innovaportal/file/3419/1/13.final-english.pdf.